The Tragedy of Richard Manuel Rewired Robbie Robertson's Songwriting Style

The Band's tender-hearted lost soul would have turned 82 today.

A First Nations-inspired cadence heralds the start of a remarkable collaborative moment, a poignant tribute to a lost friend, and a striking new career path for Robbie Robertson. “Fallen Angel,” the opening track from his long-awaited eponymous solo debut, sounds at once like an archetypical Robertson song and like nothing he’d ever done before.

His seldom-heard voice, featured only twice on a lead with the Band, begins as a spectral presence – haunted and haunting – before Robertson settles into this song’s gruffly whispered narrative. Meanwhile, a bed of layered drums (courtesy of Manu Katche and programmer Martin Page) is overlayed with atmospheric flourishes from guest keyboardist Peter Gabriel and bassist Tinker Barfield. The effect is unsettling, indeed, for anyone expecting the homespun mythology of his earlier work.

Former Band mate Garth Hudson and second guitarist Bill Dillon, who was another alumnus of the Ronnie Hawkins traveling rockabilly revues, exist somewhere deep in this song’s swirling mix – but are not prominent enough to alter its cinematically modern, wholly new environment.

Yet Robertson remained, as ever, the narrator who’d so skillfully illuminated all-but-forgotten mythical pathways with the Band, pining for a world that would never be again. That, if nothing else, was still firmly at the center of things.

The images were simple, crystalline, as a fallen angel casts a shadow against the sun. It’s already become clear just how straight-forward the emotions – if not the musical constructions – were going to be on Robbie Robertson.

With “Fallen Angel,” this album’s namesake composer showed he’d lost none of his flair for writerly detail, even as he suddenly began talking from the heart.

The memory of awful night in a Florida motel room is not summoned. Even so, “Fallen Angel” quickly reveals itself to be about what was then the defining tragedy for this often-star-crossed group. Never before had Robertson spoken with such utter frankness, with such lack of artifice – not even on more personal Band projects like 1970’s Stage Fright, which always seemed like Robertson’s overt attempt to reach the listing Manuel.

As Gabriel’s always-resonant backing vocal surrounds the chorus, it’s clear Robertson was seeking to unbind himself from the conventions of his own earlier musical successes – and yet he hadn’t completely let go of what came before, either. Robertson also seems to be reaching for a falsetto that the late Manuel previously grasped with such ease, and that makes “Fallen Angel” all the more anguished, all the more real.

Subsequent tracks on Robbie Robertson like “Sonny Got Caught in the Moonlight” are more obviously connected to his celebrated period with the Band, if only because of the notable presence of Rick Danko. Meanwhile, “Somewhere Down the Crazy River” arose out of a familiar obsession with Southern gothic iconography. But what “Fallen Angel” accomplished was altogether more memorable for this famously diffident storyteller: Robertson sorted through something locked away inside his own chest, not his head.

His transition into a more confessional approach hadn’t come easily – or cheaply. Robbie Robertson took years to complete and ran up a huge bill for Geffen Records. Along the way, however, Robertson crafted something that referenced the lyrical phraseology that had lifted his earliest work to greatness, while sharing something profoundly – and, to this point, quite surprisingly – intimate.

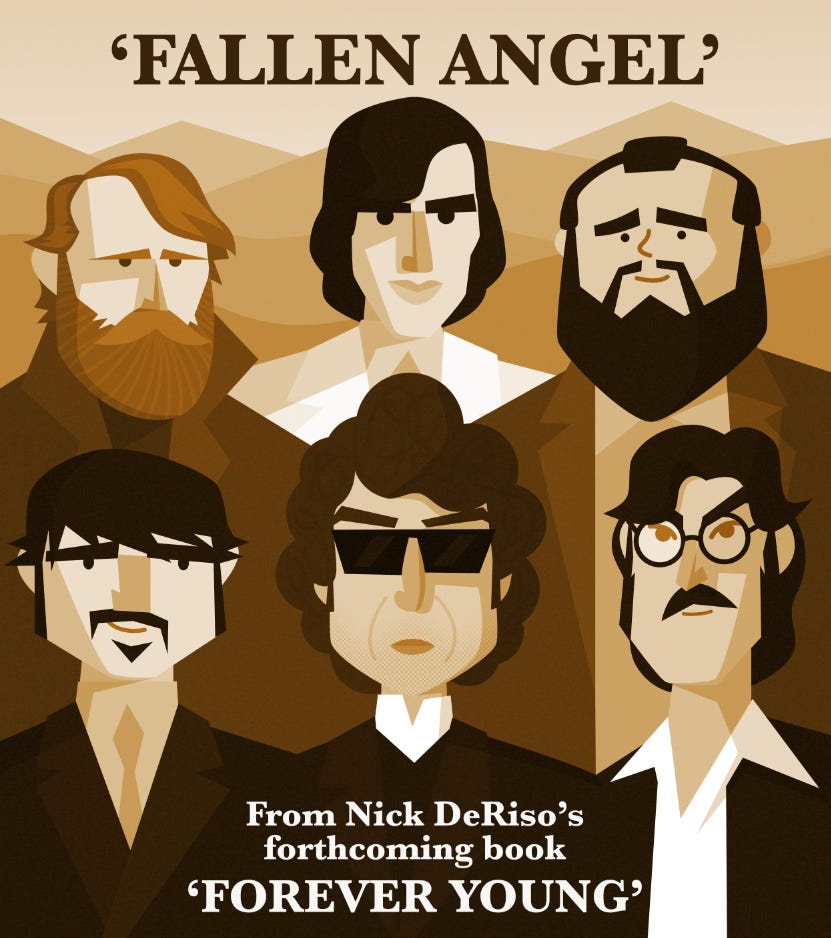

This excerpt is from Amazon best-selling rock band biographer Nick DeRiso’s next book, ‘Forever Young: How the Band and Bob Dylan Made the Only ’60s Music That Still Matters.’ It’s set for release in Spring 2025. www.nickderiso.com.

Love this.